History of Jericho

Provided by Gary Irish

Jericho was chartered on June 7, 1763 as one of the New Hampshire grants issued by Governor Benning Wentworth of New Hampshire. The town totaled 23,040 acres consisting of 72 shares. The name of the town was spelled Jerico, both in the charter and for several years in the town records. Each grantee was expected to plant five acres of land within five years for every fifty acres within his/her share. The land would be forfeited if the grantee did not continue to “improve and settle same”. All white and other pine trees were to be preserved for “masting our Royal Navy”.

Starting December 25, 1763, rent of one ear of “Indian Corn” was to be paid per year. Payment of one shilling per year was to be paid starting December 25, 1773.

The early settlers were from Connecticut and western Massachusetts. These pioneers braved this wilderness to establish their farms, homes, and businesses. The first residents were Joseph Brown and his family, who settled on the bank of a river in the northeast part of town (the river was eventually named in honor of the Brown family), soon followed by Roderick Messenger and Azariah Rood who settled on the Winooski (Onion) River in the southern part of town.

At the outbreak of the Revolutionary War, the British began to offer a bounty of either $8 or £8 (sources differ on which) to the Native Americans of Canada for each living captive from the rebellious colonies, and in 1777 Joseph Brown and his two sons were kidnapped by Native Americans loyal to Britain and taken to Isle aux Noix at the north end of Lake Champlain to a British military camp (they could not get any bounty for Mrs. Brown, so left her to care for herself). The Browns were then held prisoners in Montreal for three months, when the British decided they would not give a bounty for an old man and two boys, and they were released to return to their farm in Jericho.

On October 16, 1780, a Native American raiding party returning from a successful raid on the settlement at Royalton, Vermont came upon a young man named Gibson, who the Browns had helped to recover from typhoid fever, and who was then trapping along the Lee River. They took him prisoner, but to secure his release, he offered to show the Native Americans where they could find several people whom they could take as prisoners, thus increasing their ransom money. He guided them to the high bank above the Brown’s cabin, but once the Native Americans were assured that he had guided them to the promised spot, they seized and bound him to one of their strongest braves. The band, about 12 to 15 in number, then stealthily approached the Brown’s cabin and secured Mr. and Mrs. Brown, as well as two little girls named Blood who were visiting them from Williston, as prisoners. At the time, there was also a tailor named Olds who was at the Brown’s home sewing for the family. He spied the Native Americans approaching and was able to jump out a window and despite the arrows and tomahawks that followed him, was able to escape into the woods and make his way to the blockhouse on the Winooski River, where he reported the attack and begged the commandant to go to the Brown’s cabin or intercept the party on their way to the lake. Fearing either a ruse or through cowardice, he refused to do so. The commandant was later court martialed for his lack of action, but the result of that action is unknown.

Mrs. Brown was upstairs in the cabin when the raiders approached, and came down when she heard a great noise to find a dozen Native Americans dancing around the room. When they saw her, they gave one of their dreadful war whoops, and the leader came up to her with a long sharp knife in his hand, she supposed to cut her neck, but instead he gave a loud laugh and cut a string of gold beads that she had around her neck. He then went dancing around the room, greatly pleased that he had found such a rich treasure. Mr. Brown, who was outside, had tried to get his gun which was hanging up under the stoop on the back of the house, but several of the Native Americans came rushing out of the back door and took him prisoner. They formed a ring around him, gave several war whoops, brandishing their knives and tomahawks and seemed to be enjoying themselves very much, but did not show any desire to injure him. From their actions, and his previous experience, he believed that they were more interested in the ransom they could get than in injuring the family, so he offered no resistance. They next killed both of the Brown’s cows, their hog and all of their hens, saving the best of the meat to take with them. They then proceeded to cut open the straw and feather beds and used the ticks and blankets to tie up things they wanted to take with them. Mrs. Brown had been doing a week’s baking in the great stone oven, and had set out the loaves of bread, pies and cakes on shelves on the back stoop to cool. The Native Americans ate what they wanted, and taking what they could carry, half of the band set off for Malletts Bay, where they had left their canoes. From Gibson, the Native Americans had learned that there should be two boys as well, so the other half waited until the boys returned, when they were also captured. The Native Americans then sacked and burned the cabin and barn before following their comrades to the lake.

On their journey, the Brown family suffered much from harsh treatment, hunger and fatigue. The Brown family was always proud of the care given the two little girls by Mrs. Brown on that terrible trip. Fearing retaliation for their misdeeds from the soldiers at the fort on the Winooski, the Native Americans urged their captives to make haste, which soon tired the little girls, and hindered the advance, while the sobs of the youngest so annoyed her captors that they threatened to kill her. Foreseeing their intentions, Mrs. Brown stepped between them and their intended victim at the risk of her own safety, raised the child in her arms, stilled its crying, and prevailed upon the savages to spare her life. Again and again on the journey she carried the children when they became too tired to walk, or held them in her arms during the long hours of the night to keep them from crying. The following morning they reached the lake, where a much larger band awaited them and in canoes pushed on toward Canada. Upon arrival at St. Johns, they were sold to the British officers at $8 a head. They were then moved to Montreal, where they were at first confined with a large number of other prisoners. But scurvy soon broke out, sickness of all kinds was rife, and deaths were an everyday occurrence.

Lacking cooks for the officers’ mess, Mrs. Brown, who was known as an excellent cook, was taken from the prison camp to fill that job. Winning the good will of the officers through her cooking, she soon demanded that her family be permitted to share her labors, and this being granted they were again reunited under difficult but livable conditions. The family continued under these conditions, as servants to the British officers, for three years. At the close of the war of the Revolution in 1783, they were set free and told to go home, but they were all nearly starved and their clothes all worn out and they had no home to go to. Mr. and Mrs. Brown were also too feeble to start off on the long trip to Jericho, so the boys found a place where they could stay and do some light work to pay for their board. The boys also found some work for themselves where they could earn enough to get some good stout clothes, some boots, a couple of good guns and a good stock of ammunition, a couple of axes, and a few light necessary things that they could carry in a bundle on their backs. They then told their parents to keep up good courage and they would return for them as soon as they could get a log house built and things in such shape that they could live at their old home.

After procuring a good heavy woolen blanket for each of them to sleep in, the boys packed their things up and started off on their long trip through the woods to Jericho. After two weeks of hard tramping and living on game they could secure along the way while getting what rest they could at night on soft boughs, they finally arrived back in the old clearing. They quickly began building a small log house, planted a little corn, made a good garden and then went down to Williston, where they found that the Chittenden and Barney families had returned to their farms with quite a little stock, and many things for the comfort of their families. They let the boys have a couple of cows, two sheep, a pig, a few hens, a little flour, some corn meal and salt. They made a light sled and yoke for the cows, packed what they could on the sled and went back home feeling quite rich.

The next week they made another trip to Williston for some seed corn, some wheat, and oats, etc. They then sowed an acre of wheat, a couple acres of oats, and planted an acre of corn and more garden seed. After building a log barn so they could have a place to keep their stock safely, Charles returned to Montreal for their father and mother, while Joseph Jr. remained to take care of things at home. He worked every day, cutting brush and clearing up the land and preparing another piece for a fall crop of wheat so as to be in as good shape for the long Vermont winter which he knew would try their resources severely.

At the end of nearly a month, he rejoiced to welcome the family home once more. Thereafter, with peace having been declared, they had no further trouble with the Native Americans, nor fear of capture and the destruction of their home. Over the next few years, they continued to clear more land and improve their farm in many ways. Charles and Joseph, Jr. soon married, and the farm was divided. Charles took the northeast part, from the town line to the river, and built a house near where Browns River Middle School is located today, with his father and mother living with him. Joseph, Jr. took the south part, and built a home at what is today 17 Brown’s Trace, now the home of Mark Fasching and Christa Alexander.

History of Jericho continued

Provided by Louise Miglionico

Provided by Louise Miglionico

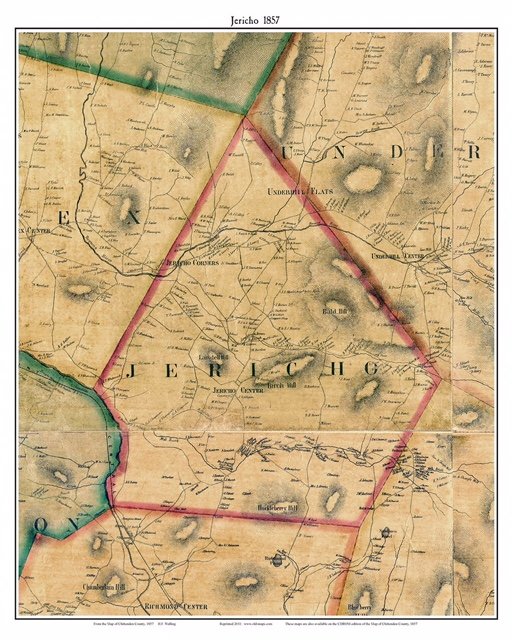

Three distinct town centers developed in Jericho:

Jericho Center, Jericho Corners and Riverside.

Jericho Center, Jericho Corners and Riverside.

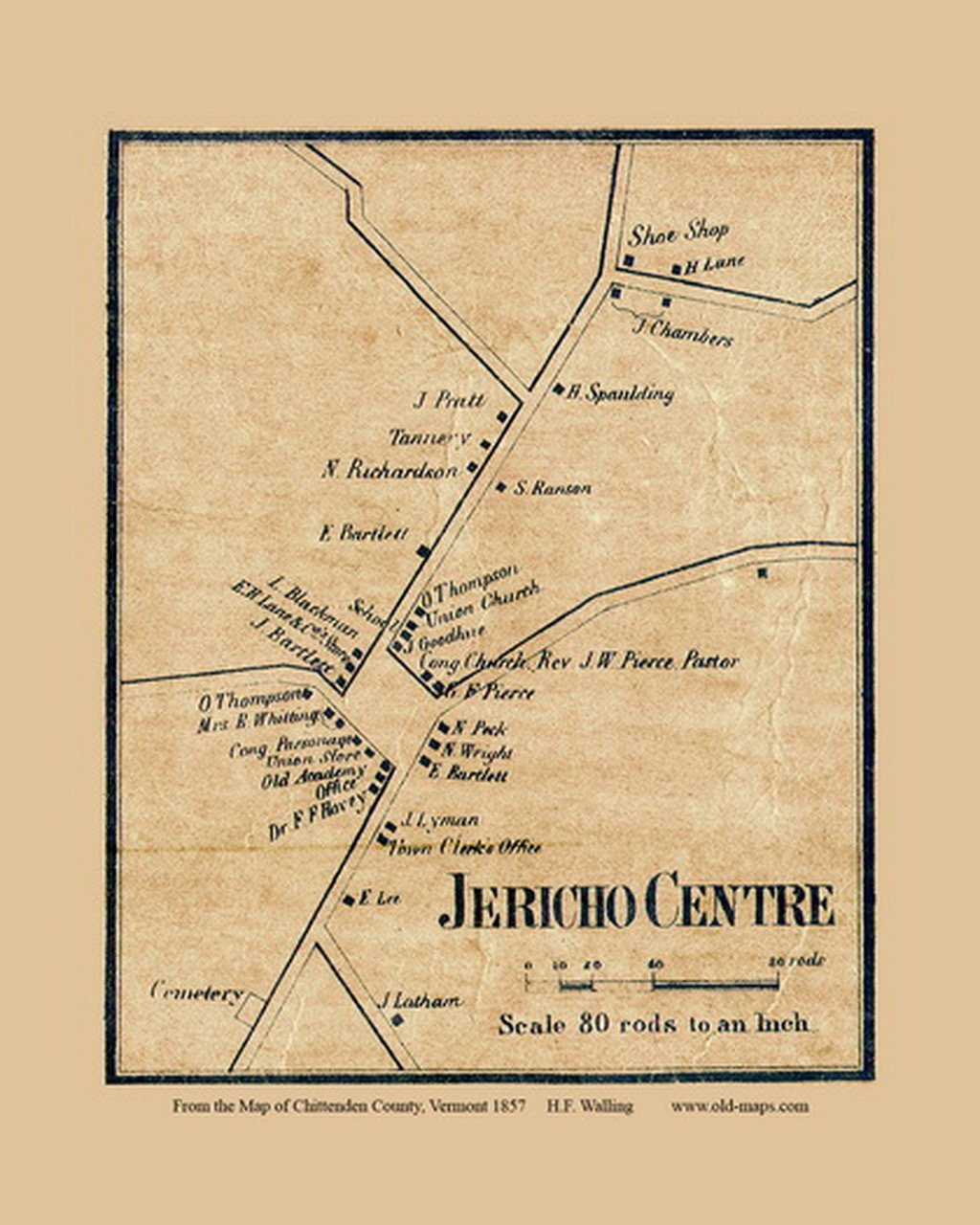

Jericho Center encompasses 17 acres located within Brown’s Trace, Bolger Hill and Varney Rds. The town green was designed and donated by Lewis Chaplin. Jericho Center became a civic center for the rural surroundings. Many of the homes are of the architectural styles favored from 1800 through 1920. The Jericho Center Country Store was first opened in 1807 as Blackman’s Store. It has changed owners many times and is one of the oldest continually operating country stores in Vermont. The Jericho Center Historic District is on the National Register of Historic Places.

Jericho Corners Historic District (also referred to as Jericho Village Historic District) is on the National Register of Historic Places It includes Route 15 , beginning stretch of Lee River Rd., beginning of Plains Rd., Mill St., beginning of Old Pump Rd. The district consists of many historic buildings constructed between 1790 and 1940. There are archaeological sites along the Brown’s River of the many water powered mills which once existed. The Chittenden Mill (Old Red Mill) still remains and is owned by the Jericho Historical Society. It draws many visitors due to its iconic beauty and history. Jericho Village once served as a stage route stop between Burlington and Lamoille County. The village is the educational, religious, and administrative center of Jericho.

Riverside town center runs along Route 15, River Rd. and Park St. The Brown family’s original cabin was in this area. The Burlington Lamoille train ran through Riverside and patrons coming to dances at the Dixon House could get off at the train there as a platform was built beside the tracks for that purpose. There were many businesses in Riverside including a steam mill, one if the largest sawmills in Northern Vermont.

Population of Jericho through the years:

1791————381

1800————728

1810————-1185

1820————-1219

1830————-1654

1840————-1684

1850————-1837

1860————-1669

1870————-1757

1880————-1687

1890————-1461

1900————-1373

1910————-1307

1930————-1091

1940————-1077

1950————-1135

1960————-1425

1979————-2343

1990————-4302

2000————-5015

2010————-5009

2020————-5104

1791————381

1800————728

1810————-1185

1820————-1219

1830————-1654

1840————-1684

1850————-1837

1860————-1669

1870————-1757

1880————-1687

1890————-1461

1900————-1373

1910————-1307

1930————-1091

1940————-1077

1950————-1135

1960————-1425

1979————-2343

1990————-4302

2000————-5015

2010————-5009

2020————-5104

From 1850 through 1950 there were numerous dairy farms in Jericho, it is said that during that period there were more cows than people. Many of the areas rock walls were erected in the late 19th century. Starting in the early 1900s , the use of barbed wire replaced the rock walls as barriers.

The number of farms in Jericho gradually diminished. Today there only two remaining, the Rawson Farm and the Davis Farm. The Jericho Underhill Land Trust and the Vermont Land Trust are working with the Davis’ to conserve 181 acres of that farm.

|

Beginning in the 1920’s, the United States government procured land in Jericho for “Fort Ethan Allen, Vermont Artillery Range”. It is now known as the Camp Ethan Allen Training Site and is a Vermont National Guard post. It houses the Army Mountain Warfare School and the 86th Infantry Combat Team.

|

|

In 1941, the University of Vermont acquired 476 acres of woodland in Jericho which became known as the Jericho Research Forest. This is UVM’s largest and most widely used forest. Courses are offered there in forestry and natural resources.

Over the years, Jericho has retained much of its charm as there are many historic buildings, beautiful natural areas, and interesting and historical sites to visit. It is a popular bedroom community to Burlington.

Sources:

- The History of Jericho, Vermont. (1916). Jericho, Vt. Historical committee and Hayden, C.H. United States: Free Press printing Company, printers.